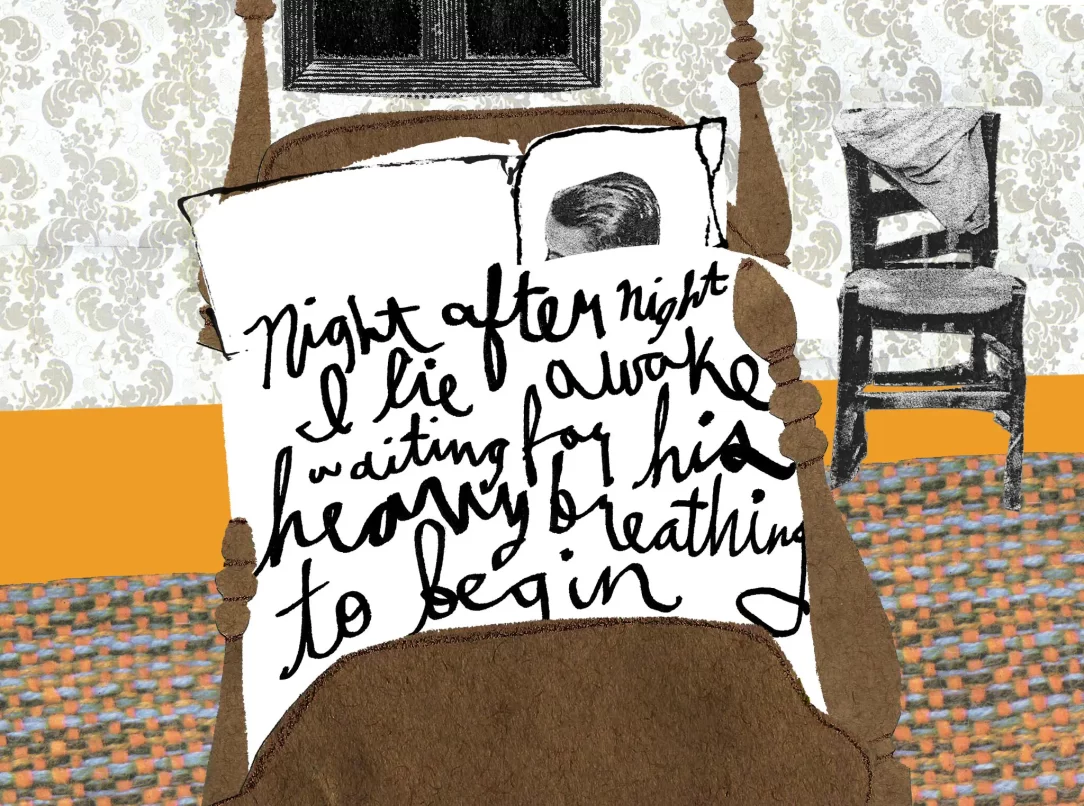

Seven decades after Millay’s death, “Rapture and Melancholy” paints a picture of artistic triumph, romantic tumult and a daily life that descended into addiction.

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was once the most famous poet in America. Her collections sold tens of thousands of copies, and her readings filled theaters from New York to Texas. She was the female voice of the Jazz Age, the New Woman incarnate whose passionate and iconoclastic verse earned her a devoted following. Her 1920 poem “First Fig” became an anthem for a generation tired of Victorian mores:

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

Millay won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1923, and at the height of her fame she seemed unstoppable. But not long after World War I, modernist poets began rejecting rigid rhyme, meter and expressions of emotion. Millay’s wildly popular love sonnets suddenly seemed quaint when set beside the oblique and somber lines of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” The modernists won the day, and the discrete, imagistic verse of Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens and Marianne Moore eventually crowded out the more decadent, romantic lyrics of Millay and Sara Teasdale. The poet Maxine Kumin remembered her Harvard professors dismissing Millay as “just a sentimental woman” in the mid-1940s.